Authors build elaborate worlds through everything from carefully-chosen foods to amateur map-making to breathtakingly detailed wikis, their attention to detail a signal that these are worlds worthy of getting lost in. Often these are specific moments in the text, or a helpful hand-drawn atlas bookending the epic adventure, or a bonus feature that’s just a click away. But some storytellers go the extra mile, embedding worldbuilding details into their texts as a sort of “found footage”—fictional childhood stories, comic books, or newspaper clippings that appear as excerpts throughout the larger work.

Sometimes, these fictions-within-fictions take on a life of their own and emerge into the real world as self-contained stories in their own right. Crack a book, cross a bridge, hop a spaceship, and check out these eight stories that are wonderfully extra when it comes to worldbuilding, creating children’s stories that can hold up to the classics, spinning off into picture books drawn from your nightmares, or even spawning entirely new book franchises. You know, like you do.

The Up-and-Under series — Middlegame by Seanan McGuire

Asphodel D. Baker is clear-eyed about her unlimited potential as an alchemist contrasted with her limitations as a human woman in 1886. She knows that her life’s purpose is to harness the balance between Logos (rational behavior) and Pathos (emotional thought), or mathematics and language, but that the undertaking is too ambitious both for her place in society and her pesky mortal coil. And so Asphodel extends herself forward through time, twofold, through the act of creation. First there is James Reed, her own personal Frankenstein’s monster, who can live over a century, imbued with her knowledge and her plan for embodying mathematics and language within flesh.

But how to shape that flesh? Here is where Asphodel’s teachings are transcribed and transformed, through the words of A. Deborah Baker. With Over the Woodward Wall, a fantastical story about two opposite-minded children whose worlds collide and then converge on the improbable road to the Impossible City. As long as publishers keep printing her book, and as long as precocious children devour the adventures of Avery and Zib, in turn seeking their own complementary soulmate somewhere out in the world, Asphodel makes her life’s work immortal. There is so much to Middlegame, so many interweaving and retconning timelines, that the sinisterly compelling passages from Over the Woodward Wall provide a strange sort of stability for Roger and Dodger, but for the reader, too.

Over the Woodward Wall was initially intended to exist only within Middlegame’s pages, but… well… sometimes a book decides what it wants to be without you. With the publication of Woodward Wall in full, readers were allowed to emulate Roger and/or Dodger in A. Deborah Baker’s beguiling tale about stepping outside of the mold of expectation and setting foot on the improbable road. This slim portal fantasy, with shades of McGuire’s Wayward Children series and The Wizard of Oz, is all about earning your ending, but even more importantly, embracing how our fellow travelers change us in the middle. Best of all, it has inspired a sequel: Along the Saltwise Sea, in which Baker will finish guiding readers through the quadrants of the Up-and-Under.

***

The Escapist — The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Clay by Michael Chabon

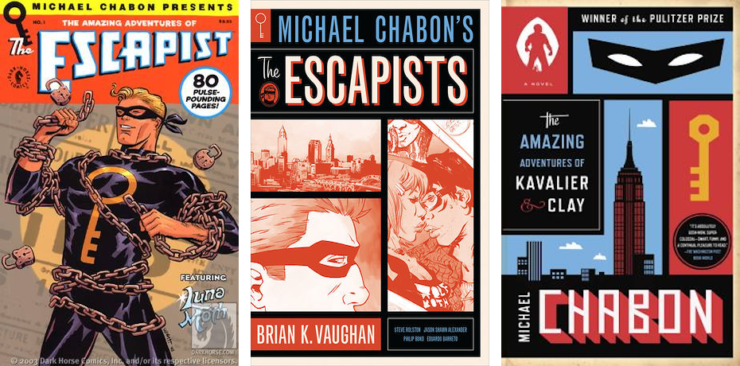

Chabon’s epic tale, The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Clay, set in the early days of comic book superheroes depicts an all-encompassing world of masked crusaders without the aid of a single image. Joe Kavalier’s arrival in New York City is fortuitous not only because he managed to smuggle himself out of Nazi-invaded Prague thanks to his Houdini-esque training in the art of chains and escape—but also because his cousin Sammy Clay is looking for an artist to help create the next Superman. Together, drawn from their own personal histories and the global turmoil swirling around them, they conjure the Escapist, an escape artist-turned-crimefighter who frees others from the chains of tyranny.

The Escapist never appears visually in the Pulitzer-winning novel—not on the cover, not in a single chapter header illustration. Yet Chabon’s descriptions of Joe’s painstakingly beautiful drawing process teams up with readers’ imaginations to construct every panel and fill it with the Escapist, the Monitor, Luna Moth, and the Iron Chain. And occasional chapter-long dives into the origin story of Tom Mayflower fill in any missing details like an expert colorist. It’s the perfect demonstration of Joe and Sammy’s complementary storytelling talents.

And what’s more, there eventually was an Escapist in all his comic book glory, in the Dark Horse anthology Michael Chabon Presents the Amazing Adventures of the Escapist and Brian K. Vaughan’s miniseries The Escapists. But by then, he already felt as familiar as the Man of Steel.

***

Tales From the Hinterland — The Hazel Wood series by Melissa Albert

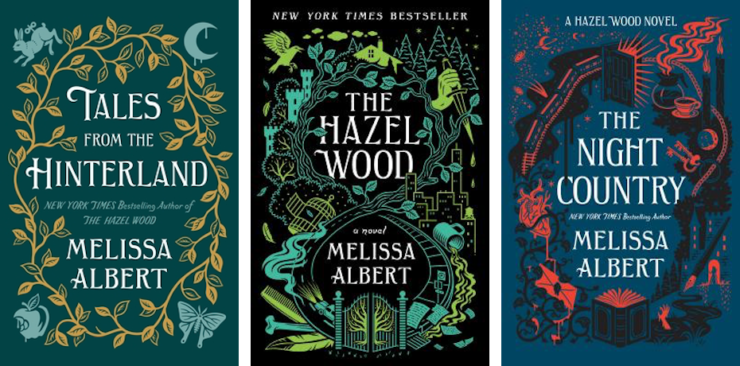

At the start of The Hazel Wood, seventeen-year-old Alice is used to running with her mother away from many things, primarily the odd bad luck that follows them no matter where they temporarily settle, and her grandmother’s literary legacy. Althea Proserpine, profiled in Vanity Fair and worshipped via dog-eared copies of Tales from the Hinterland, is known for spinning darkly compelling fairy tales and inspiring fans who can get a tad too enthusiastic when they discover that Alice is the daughter of Ella, is the daughter of Althea. But when Althea dies at her remote estate, the Hazel Wood, and Ella is snatched away by a mysterious force, Alice must confront the possibility that the Hinterland is not just a story. Or rather, it’s a story, but it’s so much more for Alice and Ellery Finch, a Hinterland superfan, to unravel.

Part of the problem is, Alice doesn’t know her Hinterland all that well, due to Ella snatching her mother’s book away with protests that the stories aren’t for children. So when Alice realizes that her answers might belong in those dozen stories—whose creatures have already begun to leave their pages for the real world—she needs Ellery to tell her them, starting with her namesake “Alice-Three-Times”: When Alice was born, her eyes were black from end to end, and the midwife didn’t stay long enough to wash her. The novel is littered with retellings like this (the paperback edition has two extra), drawing the reader into the Hinterland in the same fashion as Alice and setting the scene for her eventual tumble through the proverbial looking-glass.

While the sequel The Night Country explored the ramifications of Alice’s time in the Hinterland, Albert has also gifted readers with Tales from the Hinterland itself: an illustrated (by Jim Tierney) collection of the dozen brutal, beautiful stories that took so much from Althea and gave so much to Alice. To whet your appetite for the complete collection, you can read one of the stories now: “Twice-Killed Katherine,” starring one of the Hinterland’s most disturbingly memorable characters.

***

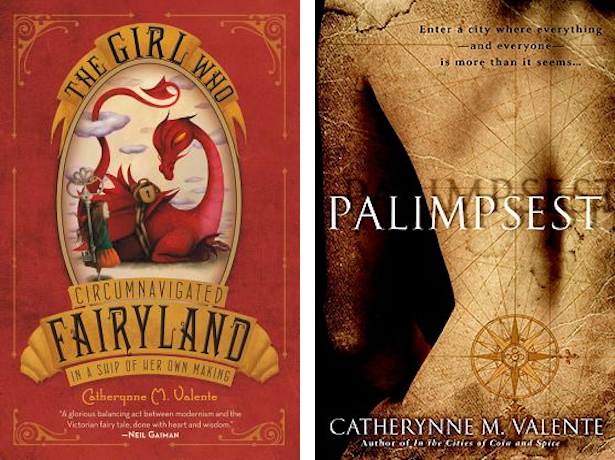

The Fairyland series — Palimpsest by Catherynne M. Valente

In Valente’s 2009 novel Palimpsest, about four travelers visiting the eponymous magical city, a woman named November recalls a cherished childhood book about a girl named September who is called to adventure in Fairyland. While The Girl Who Circumnavigated Fairyland in a Ship of Her Own Making gets only a passing mention in Palimpset, Valente was inspired to actually write the novel: September gets a visit from the Green Wind, who summons her to help manage the fickle Marquess; along the way, the twelve-year-old girl befriends the bibliophile Wyvern and a boy named Saturday.

Valente’s first foray into writing for young readers was crowd-funded, but it so resonated with readers and critics alike that it became the first self-published work to win YA’s Andre Norton Award in 2010. What’s more, it was acquired for print in 2011, featuring black-and-white illustrations from Ana Juan. The Fairyland series has since grown to include five volumes and the prequel novella The Girl Who Ruled Fairyland—For a Little While—allowing many a reader to look back nostalgically, just like November, on this ethereal series.

***

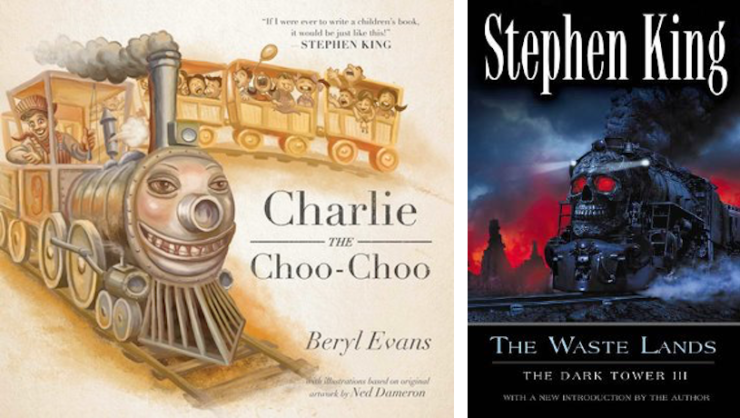

Charlie the Choo-Choo — The Dark Tower by Stephen King

Young Jake Chambers picks up a copy of Charlie the Choo-Choo, an eerie take on Thomas the Tank Engine, early on in the course of The Waste Lands, the third book in King’s Dark Tower series. The children’s picture book centers on Engineer Bob and Charlie, a seemingly friendly train with a smile that “couldn’t be trusted.” On his quest with Roland, Jake begins to notice things from the book echoed in the real world—he nearly faints when he recognizes the real Charlie at a park in Topeka.

In our world, King actually wrote a version of Charlie the Choo-Choo under the name Beryl Evans, accompanied by increasingly unsettling illustrations for maximum creepiness.

Don’t ask me silly questions, I won’t play silly games.

I’m just a simple choo-choo train, and I’ll always be the same.

I only want to race along, beneath the bright blue sky,

And be a happy choo-choo train, until the day I die.

***

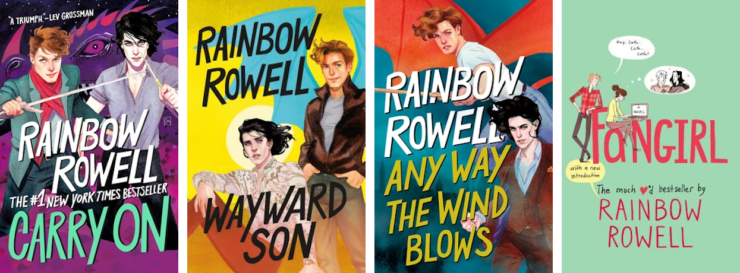

The Simon Snow series — Fangirl by Rainbow Rowell

Just as Simon Snow himself was once just words in a prophecy, “Simon Snow” the idea was, just a few years ago, a stand-in for talking about Harry Potter fanfiction without naming names. Rowell’s 2013 novel Fangirl followed twins Cath and Wren, who grew up co-writing fanfiction about their favorite boy wizard, on their first forays into college—and, for the first time, separate identities. The book is sprinkled not only with passages from Cath’s fanfic “Carry On, Simon,” but also with excerpts from the canon—that is, fictional author Gemma T. Leslie’s Simon Snow books—so that Fangirl novels could understand what foundation Cath’s writing was built on.

But what began as a plot device snowballed into its own novel, Carry On, in which a new voice tackled Simon’s story: Rowell herself. Her answer to TIME’s question about whether she would simply reuse scraps from Fangirl for Carry On reveals how seriously she considers the difference between who is telling Simon’s story: “The Simon Snow I was writing in Fangirl was a different Simon Snow. When I was writing as Gemma T. Leslie, I envisioned this feeling of British children’s literature and had a very traditional middle-grade voice. When I was writing Cath, it was more of what a talented teenage girl writing romantic fantasy would do. Neither of those voices are me. When I started writing my own Simon Snow, it was more what I would do with this character.”

Since Carry On’s publication, Rowell has remixed the Potter mythos and embarked on an all-American road trip in the sequel, Wayward Son. In 2021, she’s serving up one hell of a finale in Any Way the Wind Blows, which sees her wizarding trio of Simon, Baz, and Penelope questioning their places in the World of Mages—by extension, Rowell herself challenging the magical world she conjured out of Fangirl’s fics.

***

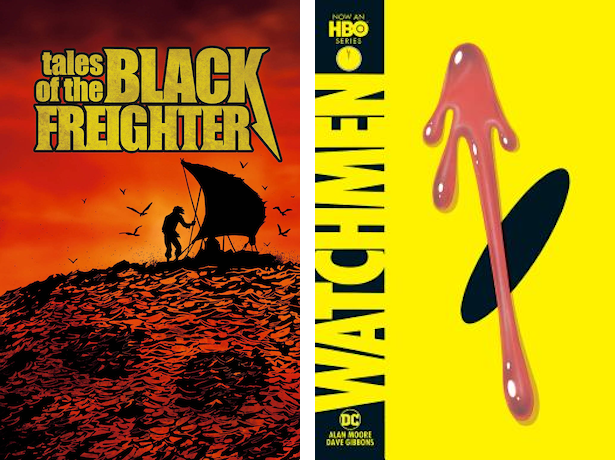

Tales of the Black Freighter — Watchmen by Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons

In Watchmen, Moore’s meticulous scripts and Gibbons’ masterful art depicts a dizzying alternate history in which superheroes have existed as part of the cultural consciousness for decades, affecting such pivotal American moments as the Vietnam War and Richard Nixon’s presidency. But what really shores up Moore’s vision of a world inhabited by caped crusaders are the chapters from Under the Hood, the autobiography of Hollis Mason a.k.a. the original Nite Owl. These passages bookend the first few issues, along with in-universe articles and other pieces of prose text that provide stark contrast to the comic book pages. And these bits of worldbuilding almost didn’t even exist! Moore and editor Len Wein have both explained how DC was unable to sell ads for the back pages of each issue; rather than fill those 8-9 extra pages with what Moore described as “something self-congratulatory that tells all the readers how wonderful and clever we all are for thinking up all that,” instead they displayed their cleverness through prose.

Also interspersed throughout Watchmen is Tales of the Black Freighter, a fictional pirate comic that pays homage to The Rime of the Ancient Mariner and Bertolt Brecht’s Threepenny Opera. Because in the world of Watchmen, it stands to reason that the average person has little need to read superhero comics when heroes, in all their triumphs and defeats, are part of their everyday life—which means that epic sea tales reign supreme on the comic book racks. And it can’t just be a one-page Easter egg; it must be an entire issue, spread over the narrative, so that the reader can fully appreciate the devastating conclusion to both comic-book stories when they hit at the same agonizing moment.

***

What are your favorite worldbuilding details that took on a life of their own?

An earlier version was originally published in May 2019.

Natalie Zutter applauds all these authors for their narrative nesting dolls, as she grapples with doing the same in her own fantasy novel. Talk worldbuilding with her on Twitter!